Essays

Obituary for Beverly: A Photographic Essay

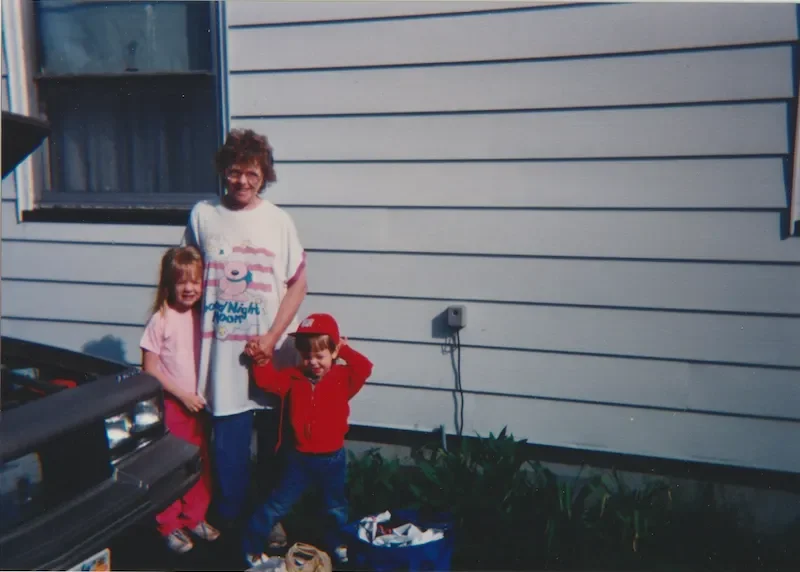

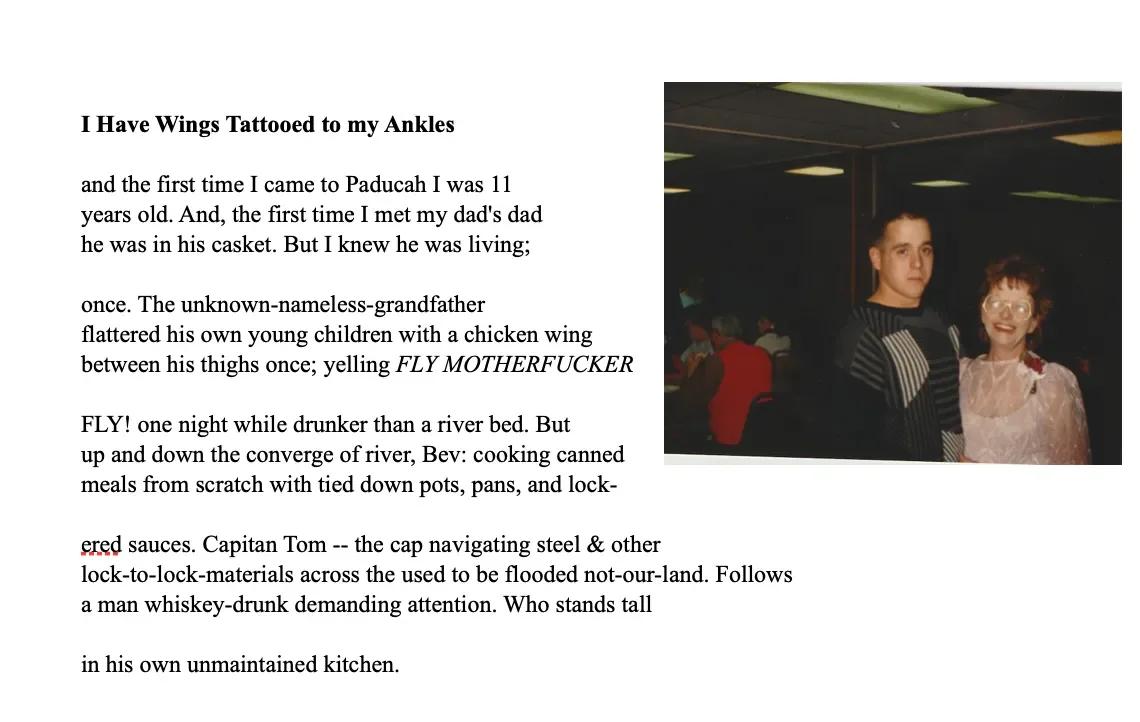

A woman stands frozen in the light of the flash of a 1990’s disposable camera. Her eyes struck still in the surprising shutter that captures her life in one single frame. The bulb illuminates the dirty glass in the background of the photograph. Her big round glasses help to fixate upon the stunned look of her pupils and the frustration of a surprise soul-stealing collapse of the camera shutter. She’s wearing a white collard shirt often seen worn by waitresses who smoke cigarettes while taking the order of grumpy and misogynistic men at 3 a.m. in the confines of a smoke yellow-stained diner. She’s carrying a thin-strapped purse around her tiny shoulders that’s likely carrying her essential belongings, Pall Mall Lite 100’s, Winterfresh Spearmint gum, mediocre tips collected from the long night shift, and probably a pocket knife. She looks tired in this photograph, the wrinkled face of an overworked woman in Middle-America, and a woman who has raised too many kids on her own. The photo reads like a missing person's alert, someone someone is trying to find; missing in action.

Her name is Beverly, or as most called her, Bev and she is my Grandmother. In her house in Galesburg, IL, in the 70’s she paid the bills, she worked jobs in diners, in restaurants, sometimes doubled as chef and server. Bev found herself at Pizza House, Koddle House, and her own house to provide for three young fatherless, or father-absent boys. Bev held many positions in the working-class industry of the regional area of the Mississippi Valley stretching from the convergence of river in the Ohio & Mississippi waters in Paducah, flowing north upriver into West-central Illinois and Eastern Iowa. According to her official obituary:

“She was a Carman for Burlington Northern/Santa Fe Rail Road in Galesburg for several years. She was also a cook for the Ingram Barge Company in Paducah, Kentucky. She was a member of First Lutheran Church in Galesburg. She was an active member and former president of O.A.K.S. in Galesburg where she loved to cook and bake for others”

And, yet, this doesn’t seem to be enough about a person's life. Bev, according to accounts I’ve heard was the first woman to work for Burlington Northern’s Chicago division as a Carman. Preceding another woman at the same time by records. She got the job because she showed up to the rail hail every week until they couldn’t say no any longer. Testimonies that even in short do more justice to the life of working people than the monetary writing of an obituary. But when a person dies we are no longer able to communicate with them. And in my case, all I have are a few snapped photos of Bev. These circumstances have directly inspired me to do this work.

For years it seemed that these photos would be meaningless in their plastic-wrapped pages, poorly written dates on the backs, collecting the dust of our lives in the back of grandmas closet. But ever since grandma died, alone, in a Peoria hospital, those photos are all I can muster to grasp at for any sense of solace, an answer, or just a moment of closure.

There aren’t many pictures of Bev and the pictures that do exist are ones that I imagine she wasn’t all too happy to be a part of. Over and over again her gaze seems to criminalize the act of the photograph. In the moments where the nameless or unknown camera operator claims her body in the gestural manner of photography, Beverly seems to be in transition, or more often a disposition. The details of the pictures themselves don’t leave much to garner about any of the artifacts or production of the image. Just like when grandma Bev passed away alone in a hospital bed in Peoria at the early height of a pandemic these photos leave more questions than answers. More pondering than closure. I’ve been having family members send me photos of Bev. Which I have been scanning and creating digital negatives out of and then creating cyanotypes. But why? What the hell for?

What we see in a photo can easily be applied within the realm of textual analysis. Often we see this type of analysis applied to high art photography, or gallery art photography. Yet, there seems to be an untapped world of photos sitting in many western homes. The family albums stacked up in closets, sitting on coffee tables, and the ones of importance framed hanging on walls. Marianne Hirsch a scholar of history, the holocaust, and a post-generation holocaust survivor herself has been studying the textual implications of her own family photos for years. She’s written two books on such a subject and although, I am not nearly in the scenario that Hirsch is in as a post-generation academic, I do find many of her attributions to the study of photography to be applicable here in these cyanotypes I am creating from old family portraits. Much like understanding the process and archival desires of 19th-century images, there is a severe lack of information regarding each image. The unawareness and speculative fascination of the early developments of the image in the western world must have been so powerful that indeed there aren’t names to go with the images we engage with from the period. So, what do we do with images that cannot be documented, archived, or traced back as an abandoned skeleton buried deep in the ground? We begin to read the image.

The first testimonial encounter that Hirsch arrives at is a photo of her parents, her father is brandishing the star of David on his coat, the young couple is on a city street, they are free to be people but are restricted from privacy in the public space, strongly suggesting that the Nazi’s have occupied this region of Europe due to Hirsch’s father’s marking on his clothing. A time before the massacre, but not so soon before. A frozen moment that captures the heavy casualness of war, of genocide, of public apathy, arriving from a seemingly innocent portrait of a young Jewish couple walking the streets of Ukraine. This type of horror is not clearly seen within the confines of the photograph. Yet, there’s a nearly invisible cruelty contained within the subjects of the picture.

“However small and blurred, however seemingly incongruous, it was a valuable piece of evidence that, we hoped, would give us some greater insight into the texture of wartime Jewish life in this city. Eager for it to reveal itself even more to us, we digitally scanned and enlarged it, blowing it up several times, searching to find what might not be visible to the naked eye. . . All of a sudden, it looked like there was something on Carl Hirsch’s left lapel that had not been noticeable before. A bright light spot, not too large, emerged just in the place where Jews would have worn the yellow star in the spring or fall of 1942.” — Hirsch “What’s Wrong With This Picture”

With this in consideration about the textual spectrum of Hirsch’s family portraits, what cruelty lay invisible within the images of our own families? For Bev’s life that cruelty surely resided in the working institutions of her time on earth. Whether it is cooking in a barge kitchen tugging up the waters of Western Illinois, south towards New Orleans, or the rail yards as a woman in the 70’s in Galesburg, there must’ve been (along with love and joy) an invisible hardship hiding right within the frame. And, all I, and we have are these few starkly strange photographs.

In the 19th century when photography was still a cross-section of art and science and mostly speculation, the apparatus of the camera didn’t allow for efficient portrait making. Many portraits were blurry and out of focus. Exposure times in such an era begged subjects to sit still for 15 minutes, an impossible task. The ghostly cast of the portraits from that era is enchantingly haunting, pure, and infinitely curious. The wondrous modes of creation have seemed to muster some sort of desire within me to use, to appropriate, and to honor the blurry photos created by my family even 100 years after Niepce’s and the world’s first encounter with such imagery. Other than apparatus, and science, what was it that Niepce was trying to capture? Why did he choose to aim his machine towards his family estate “Le Gras”? There is heavy documentation that it likely took Niepce over 8 hours to expose his first photograph; a landscape. But I wonder what Niepce desired to photograph first? Were there blurry washed out portraits of his family before the world ever saw Le Gras? It strikes me in this investigation that not much has changed about the relationship to the apparatus and the gaze of western culture. The obsession with the portrait has many modalities. I find the seemingly external need to photograph another could easily be seen as a desire to look into one’s self. To externalize the need to see ourselves and to see each other.

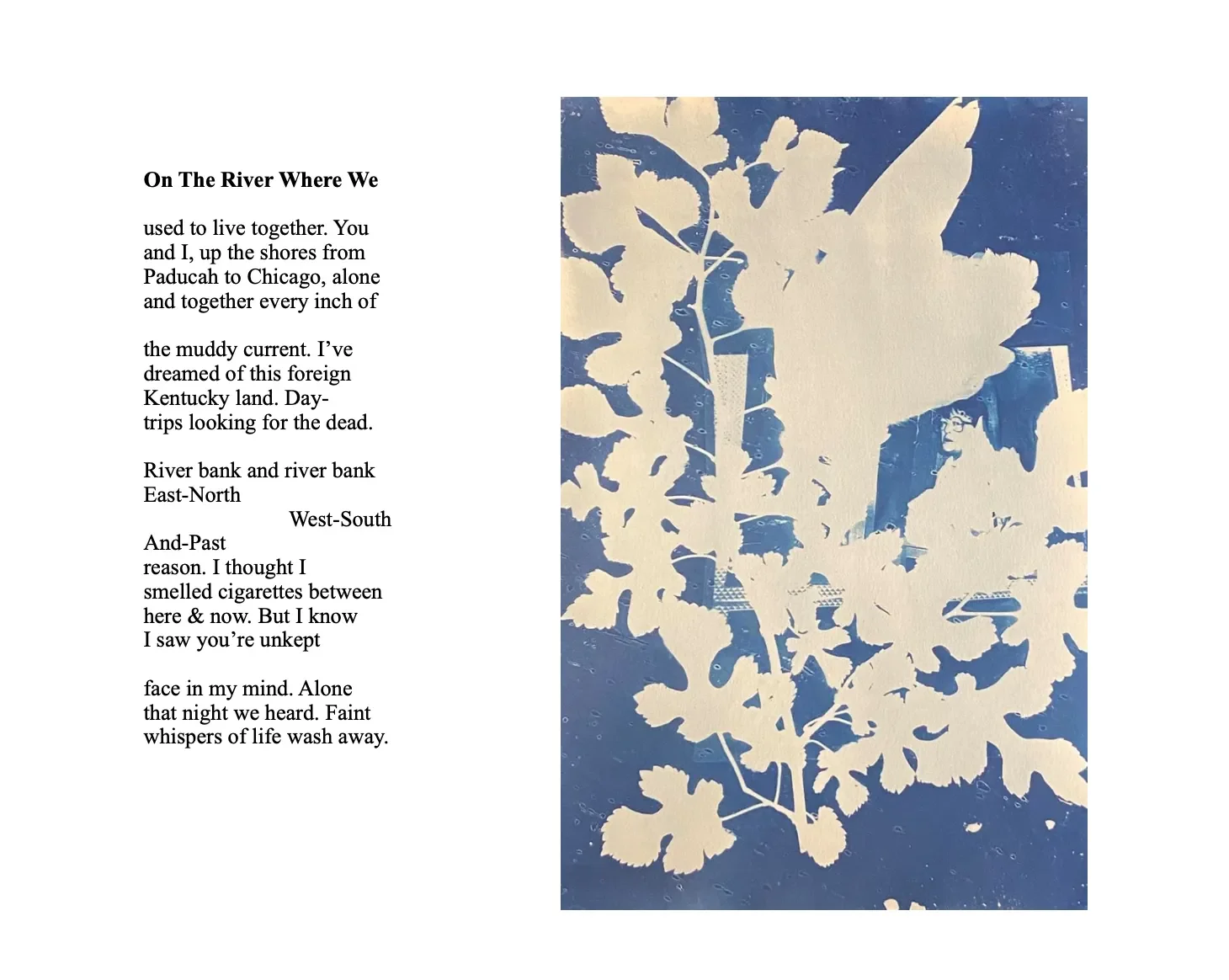

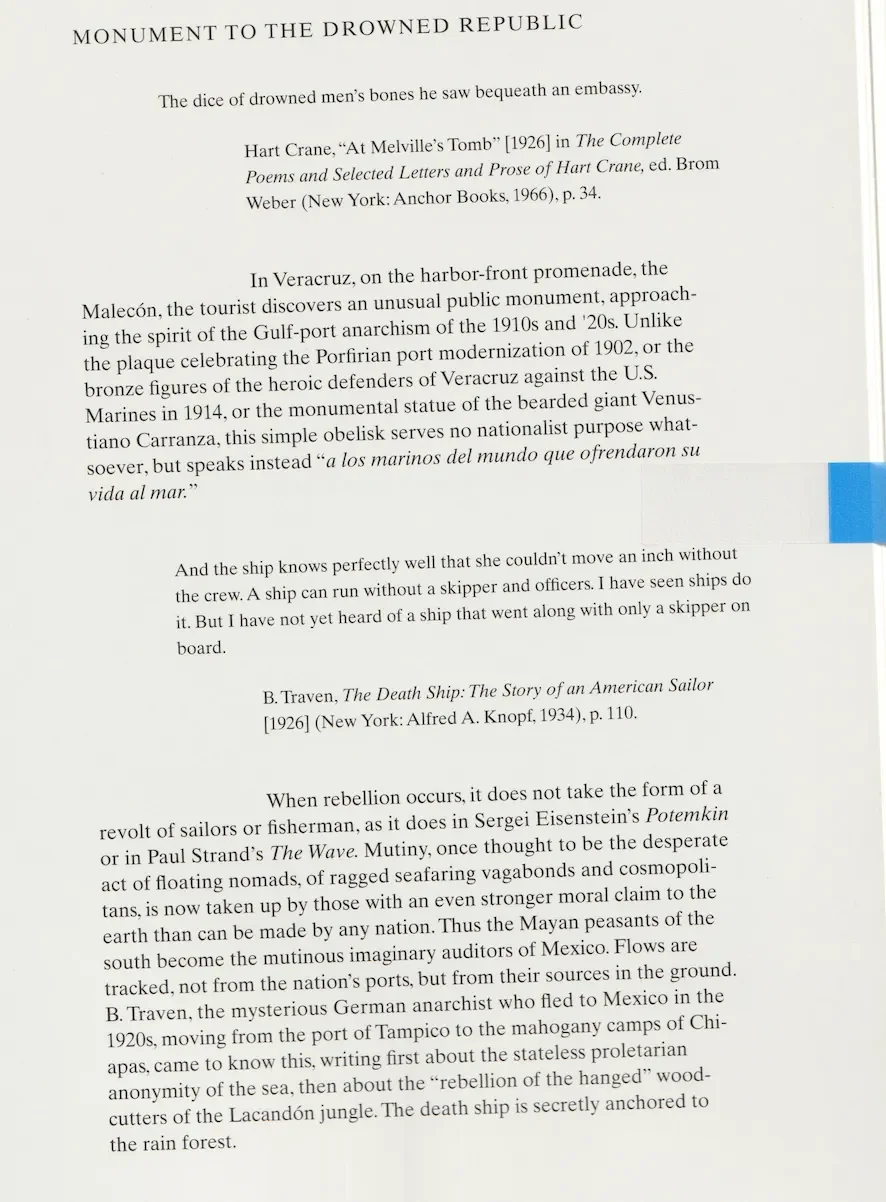

In the photographic essay book, Fish Story Allan Sekula investigates the invisibility of the maritime space on earth. Sekula photographs ship workers, he writes poetry based on their testimony and tabulates historical essays about what he calls The Forgotten Space. In this poem Sekula engages with a monument to the dead:

This poem speaks to the monument of workers, of labor, and the horrific nature of the movement of ships. For, without workers, there is no labor. Sekula’s work provides a space and ability to create such monuments for working-class people of my life. This essay is an attempt at a monument like the one Sekula speaks of. A teardrop in the ocean of tears that serves to celebrate the many working people of the world.

Bev was a force in the kitchen. She occupied her house with an entire restaurant catalog of cooking equipment, recipes in the thousands, and three refrigerators. The last time I spoke to her on the phone it was late March when the United States had been put on lockdown. I hadn’t seen her since that previous Thanksgiving, and I was a few weeks out from recovering after a long trip to India. I had missed her for Christmas and her son (my dad) died a few years before, so I knew she would likely be alone. Bev still cooked like she was on the barge feeding the captains, officers, and ship hands. And, the holidays were no different. It was as if she longed for a big family meal, like the ones she may have had as a child on the dirt farm in central Illinois or the meal she desired to have and dreamed of. Where no one left hungry, and there was enough to take home in CoolWhip containers, a world where there is always room for pie, and seconds, and thirds. A world where everyone can stay longer, where we can meet together, and there’s always winter fresh gum to fresh our garlicky mouths, and maybe even a cigarette for those who partake. On the phone, we talked about being safe, about not going out unless needed, and when I told her I could arrange someone to bring her food if desired she declined. I was worried that she would succumb to the virus and that selfishly I would never eat at her tiny dinner table again. No more pecan pie, or soft hugs, or fudge.

And, in a state of tragic events, Bev found herself in the hospital alone. The hospitals were closed to the public for any reason at all. I was only a few short hours away near Paducah, and near Peoria, and still not near enough to my dying Grandmother. Bev passed away alone on April 11th shortly after the nurses put the phone near her lifeless body one last time in an attempt to preserve some amount of normalcy in the midst of tragedy. My sister was on the other line at that time and spoke to Bev without a response. When I got the call I found myself with nothing more to do than open a beer and watch a John Wayne film in an attempt to celebrate, to reprive, and to mourn Bev. I don’t know what she would have wanted because I never asked.

This screenshot of the funeral from Facebook Live is all I have in regards to closure. These limitations have led me to create this form of an obituary. I don’t imagine that this document is complete though. I am finding ways to keep this work open, the work of celebration, of seeing, and lengths to understand the imagery of life and in death. I hope that somewhere Bev is smoking a pall mall, and is being served well by her makers. I do know that we have these photos, these stories, and preservations of a life worth talking about.

For Beverly Tracy - 1942-2020

Broken Hands In Wataga, Illinois;

During Sunset

The cars were cheap.

Maybe $200 bucks.

The kittens were the only thing that thrived in that garage, in that long warehouse on the prairie of Illinois. Cat litter sprinkled across the concrete floor soaked up oil from the cars we tore apart. Kittens that seemed to grow straight from that ground bounced around and were expendable just like everything else in the shop. If one of the kittens died no one would blink an eye. Just like the caged rabbits in the back of the garage, none of the kittens had names. We didn’t name the cars or show up sober. A hangover after a late night at John’s house or the pills Sam was taking or the weed we smoked from Galesburg to Wataga. I needed money more than anything in the world. Gas was five dollars a gallon. Every regular job that I applied for--the fast food joint, the retail store, the gas station—was was held by someone well into their fifties, who needed the money more than I did. I was under qualified and too young to work in a country that had just destroyed the entire housing market. My Grandpa would typically remark in those times,“He’d pick up chicken shit if he had to. Wouldn’t he?” And that was the endearing truth.

There ain’t a lot of pride in one’s employment as a 17-year-old kid with long hair looking to buy his next pack of smokes and a little bit of gas. Besides, in the light of the largest recession this country had seen since the Great Depression, work was work. I come from labor families. Generation after generation of hard work and shit pay. Bricklayers, pipe-fitters, ironworkers, me: a car stripper.

The worksite was a dilapidated old barn turned garage in Wataga, Illinois. The boss, Andy, would take us to the old farmer's fields around the tri-county area. Andy was an average sized guy with a typical midwestern belly, a not so sharp goatee wrapped around his mouth and had a terrible addiction to smoking low level weed out of a one hitter every ten minutes. He sported dirty white t-shirts tucked in under a belt and blue jeans that flowed to the bottom of his legs right on top of his boots. Andy snickered and stammered inaudible remarks or inside jokes that were indeed inside. Nobody knew what he was talking about. Andy, who was about thirty-five at the time, would find cars that had been left in lots, left in tall un-kept prairie grass, left in the industry of archaic farming days. We’d pick up broke down and rusted up cars for absolutely nothing. We: a slew of strange lowlifes stuck in the ass end of economic collapse. John would strap the cars up to the hitch. Sam would smoke a cigarette and talk shit while the rest of us did the work. Then Mike and I would push the old rusted car from its thought of eternal grave onto the trailer and secure it for country roads. Then back to the garage. The business involved me and a ramshackle group of rednecks tearing down cars to every minute piece imaginable. Piece by piece, from door handle, to passenger side front head lamp, to driver side seat belt, to rims of an ‘87 Camaro. Andy made us clean every single piece, take a photo, inventory it, and he would sell them all online. Small transactions. eBay days. A door handle of a 94’ Dodge Caravan was worth about three bucks. But when the whole car was purchased for $200 bucks and sold part by part, he could sometimes clear $1000.

My hourly value was about the worth of a door handle on a 94’ Dodge Caravan. He meant well, the boss that is. I got paid whenever there was money. I washed and polished parts till my hands bled. The hands that wished upon me work and confirmation. In the cold winter air of the prairie, I worked till my skin fell off, till my pride was a the value of the old family van sittin’ behind the barn with grass grown up to the windshield. I knew I had fallen into the trap-of world, society, people, economy.

Car stripping wasn’t the only endeavor the boss had. With his uncanny ability in enterprise, business, and wit, he found his hands in many pots. One was selling a variety of rabbits out the back of the garage. French lops the size of a small dog. Fuzzy lops that were bushy and frail. Pygmy rabbits. All kinds. I never got too acquainted with the rabbits. They were just another commodity like the cars, the workers, and the kittens. The rabbits sat in a 15 x 15 metal cage with individual boxes for each one of them. The container held from anywhere 10 - 20 rabbits on a given day, depending on how many died overnight. At the time I was working, the facility was a disastrous environment for rabbits, humans, cats, and cars. It certainly did not contain any heating units. The best chances for warmth were gloves, coats, and boots. So, as one would imagine, we would find dead rabbits in their cages every morning laying solemn, strange, and frozen next to their icy bowls of water. It didn’t bother me much at the time, this was not my game, my game was cars, not some silly rabbit.

.The first time I went camping in the woods of the Illinois prairie was with my Grandfather. Somewhere on the outskirts of the Mississippi River amongst mosquitoes, bees, ticks, and family we caught fish and built fires. I was barely tall enough to reach the handle of the bright red Chevy Suburban that caravanned me, my cousins, and Grandpa down to the creek. About 15 of us would load up in trucks and SUVs with pocket knives and flashlights. We’d park the trucks about a mile from the water, walk into the woods with equipment on our backs, catch fish, and sit around the campfire. Folks who would in one minute shoot a squirrel, fry it up, and then in the next, walk past the campfire, butt naked, in an attempt to provoke a laugh out of all the boys. Strong men, mostly labor, and mostly military. The type of guys who talk shit, drink, and smoke cigarettes. Not the men they are any more. I’m talking back when the economy was good, Clinton was in office, and the factory was still in town. I’m talking before I ever had to worry about getting a job or buying cigarettes.

We would seine for minnows under an overpass next to the cow pasture near by. Us kids were useful in those moments because we could sneak under the electrically charged herd fences without getting shocked. The minnows were used for bait to set bank poles with. We would set poles in the wet mud banks of the creek. Which meant getting in the water fully clothed and shoving PVC pipe line with a hook and bait into the muddy banks of Henderson Creek. At night we had to watch the poles with flashlights to see if a fish was on. If they were, it was time to get in the water. We would cripple in the cold water with life jackets on bobbing up to the top. Usually the kid duty was at night time when the old men were too tired or drunk to get in the water. We didn’t mind as kids. Besides it was the best time of the night to harvest fish.

We’d keep the fish alive in wire baskets submerged in water and fastened to the sandy banks of the creek until it was time to pack up and leave. Then the abundant amount of catfish that the water had granted us needed to be processed. Near the water’s edge on the sandbar of Henderson Creek my grandfather handed me a sharp fillet knife. This was the first time that I had ever held a fish in my hand. I had never killed an animal before, nor, had the thought beckoned me. But I knew that in the tradition of the family and the way my grandfather looked at me, cleaning a fish would prove my willingness to survive. We started with the sharp blade barely below my fingers as I held the catfish, as I began to slice the under belly, as I slowly moved to slice the head of the fish and watched the blood start to pour. The dead-eyed glance of the creature looked right into my eyes and I knew in that moment that killing was not “okay” but that survival and trade and death were necessary. After the slice had been made around the entire head of the fish, it was time to skin it. With a primal looking style of pliers he showed me how to toss the skin back into the creek and respect of the water around me. We filleted the sides of meat off of the gift given fish and cleaned it in the water we drug it from. He showed me where to slice the skin, how to pull the skin off of the fish with pliers. Cut the fillets and bury the remains. How to bury the perfect creature deep to nurture the earth’s soil.

The kid at the garage who was in charge of dealing with the dead rabbits was the son of the owner and just 5 years old. His name was Jake. He would frantically scour through the mass of caged bunnies in hopes of a dead lop, hair, or jack. I mean Jake was really excited about his given duty. And when he found one, the whole garage new, the block, the neighbors, the next county even. The boy would come charging from the back of the garage between two massive aluminum doors where the bunnies lay, screaming in excitement, championing the dead hare in his hands, grasping the fellow animal by the legs, and would soon, after showing off his find, charge to the burn pile in the back, with gleaming eyes and fire reflecting from his pupils. I would watch the child glow as his prize burned in the flames before him.

We were all numb in that garage--from weather and uncertainty about the future. There was a collective of guys who came in and out of the garage over the few months I spent there. It wasn’t a bad work environment. But there was never a thought that we would ever make enough cash to do anything but by the things that were temporary. We were flat, covered in oil, dead in the eye with broken hands, and bad habits.

Jon was an ex-con who had been imprisoned for fire-bombing someone's house. And every time he worked on cars he would get pissed off and start throwing wrenches. That didn’t make Andy very pleased. He lived on the property in a hallway turned into an absurd apartment. Sam and I used to hang out in there. We had to turn the oven on and open the door to heat the meager excuse for a kitchen. Sam was the one who got us all into this mess. He promised good pay, and cigarettes for the trouble. But the pay rarely came. Which was difficult for all of us. Especially for Mike, this Latino guy who had just left the Marines and didn’t have a shot at getting a job. He did a tour in Iraq and was in a battle over child custody. Mike never talked much any barely gave us the time of day. He was somber and quiet as we tore apart the work that could have been done building new cars not tearing apart old ones. He used to wear his fatigues while we tore apart the cars and complain all the time. I thought he was a real wuss but didn’t realize until a bit later that this guy was really getting fucked.

So when things were getting bad and none of us were having a day that was cooperating, we would sneak in to Jon’s apartment to smoke the pound of weed he had stolen from his brother. Sit and talk shit to each other. Rick would always show up to bother us. He was this older guy probably about 50. He had a lisp that made every “r” sound like “w.” White and wiry. His voice sounded like a squeaky mouse. Long whiskers in white hanging from his lip and head. He looked like Yosemite Sam. The ring tone on his phone was Katy Perry’s “I kissed a girl and I liked it.” Rick would wait till the last possible second to answer his flip phone so that he could eat up every last bit of the song. I think he un-ironically enjoyed it. I had no idea why he was ever at the shop.

I remember the smells of pig shit that would roam the entire neighborhood. The smell of gasoline and the absurd ways to make a transaction. I come from the crop of shit work for shit pay. I did not know that until I began stripping cars apart in Wataga, Illinois. I did not know that I wasn’t alone in the game of the next dollar until I met those folk.

But being trapped in a shit economy in Nowhere, Illinois didn’t give much time to be particular about what business practices were being passed on. There were worse things going on. There wasn’t much difference between Jake’s understanding about life and death and mine. He saw the death of a rabbit as a part of life and kept on moving. I learned how to kill an animal and properly process it.

Just like I saw the labor world as just a part of life. My entire family lineage had been dealt this hand. They knew the Jon’s and Rick’s of the world and had known of them for a long time. I kept telling myself at 17 that “school just wasn’t for me” and the people around me grew to accept and encourage that. My mother used to say to me all the time

“You just don’t seem like the college type.”

And I would think to myself

“Well, ok, guess I’m the car stripping type.”

Whatever the hell that meant. I dropped out of college soon after starting this glorious short term job in a garage in Nowhere, Illinois. Then I quit that job too. Ended up taking a job at McDonald’s where I was faced with frying more chicken and fish than I had ever seen in my life. And years of food service after that. Mass food service. The labor changed but the ideals didn’t. We were broken like the rest of the people before us and stuck in a garage tearing apart the world.